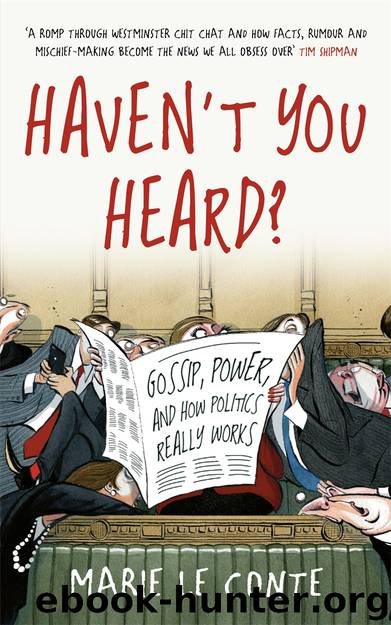

Haven't You Heard by Marie Le Conte

Author:Marie Le Conte

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Blink Publishing

Published: 2019-11-15T00:00:00+00:00

LOOKING FOR TROUBLE

We’ve established that newspapers will publish gossip if it is indicative of someone’s character or, more generally, has a wider meaning. What we haven’t discussed so far is political gossip that is just that: an amusing or scandalous piece of information that serves no real purpose besides its entertainment value. It has a fine (if controversial) history in newspapers, and can all be tracked down to one man: James Gordon Bennett Sr.

According to Joel Wiener’s The Americanization of the British Press, Bennett launched the New York Herald in 1835 at a time when political reporters were told to provide ‘no insight into what transpired behind the scenes at the national capital’, and turned everything on its head. The Herald dedicated many of its inches to ‘gossip and chat’, to the delight of its readers, and jealous competitors soon launched their own ‘Washington Letters’, as they were called at the time.

The format was a ‘frothy concoction of social and political information’, and crossed the Atlantic not long afterwards. One of the people responsible for the move was T.P. O’Connor, without whom Westminster may not have been infected by Washington’s tittle-tattle obsession. The political journalist was also an MP and wrote in 1889 that ‘everything that can be talked about can also be written about […] No one’s life is now private; the private dinner party, the intimate conversation, all are told.’

Though O’Connor’s beliefs on privacy rights (or the lack thereof) helped create the environment we have today, circumstances also had their part to play. Until 1881, provincial newspaper journalists weren’t allowed to sit in the Press Gallery in Parliament with their London counterparts, meaning that they couldn’t do any first-hand reporting of speeches and debates in the House of Commons. Resourceful as always, the hacks decided to instead specialise in ‘descriptive’ political gossip, while the London papers wrote about parliamentary proceedings. The journalists were eventually allowed to join the Gallery, but the revolution had already started.

It eventually blossomed in 1916 with the creation of the ‘Londoner’s Diary’, a collection of three daily columns written ‘by gentlemen for gentlemen’ in the Evening Standard and described as a ‘daily causerie of the world, the flesh and the city’. The rest of the trade sharply followed once more, and according to H Simonis’ The Street of Ink, it was remarked only a year later that ‘the best tribute to the “Londoner’s Diary” is the fact that it now has its counterpart in the other penny evening papers in London’. Intended as a repository for gossip, the diaries quickly became one of the most powerful parts of newspapers: more than frivolous entertainment, whispers and rumours could also be used to enhance one’s status in society, as well as building people up and knocking them back down.

Press baron and then-owner of the paper Lord Beaverbrook was even said to have regarded the ‘Londoner’ as ‘his own personal fiefdom, an armoury from which he could seize a weapon at will; bludgeon, cudgel and rapier lay

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18975)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12172)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8858)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6848)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6233)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5747)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5694)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5476)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5398)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5186)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5122)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5060)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4926)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4890)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4747)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4714)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4665)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4477)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4464)